《茉莉花在中国》(下)电子版

9 12月

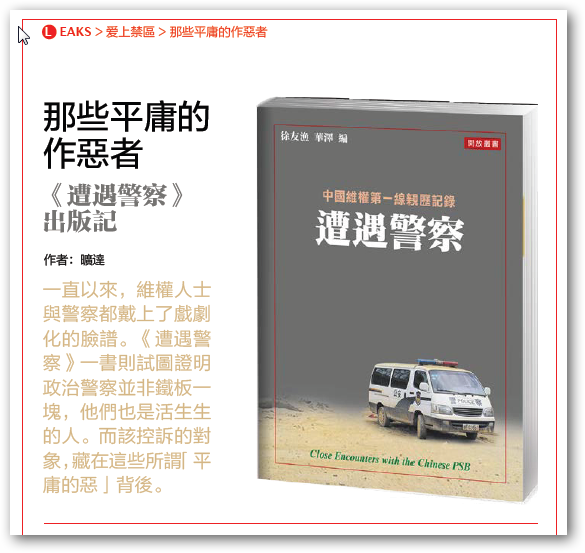

11 11月

The New York Review of Books:

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2013/nov/07/how-deal-chinese-police/

In the Shadow of the Rising Dragon: Stories of Repression in the New China

edited by Xu Youyu and Hua Ze, translated from the Chinese by Stacy Mosher

Palgrave Macmillan, 236 pp., $16.00 (paper)

Zaoyu jingcha: Zhongguo weiquan diyixian qinli gushi [Encounters with the Chinese Police: Stories of Personal Experience at the First Line of Defense of Chinese Rights]

edited by Xu Youyu and Hua Ze

Hong Kong: Kaifeng chubanshe, 370 pp., HK $100.00

An umbrella salesman being arrested by two plainclothes officers a moment after unfurling an apparently apolitical, sports-related banner in front of the Shanghai World Expo (hoping it would be captured by the foreign photographer who was nearby), April 2010

A casual visitor to China today does not get the impression of a police state. Life bustles along as people pursue work, fashion, sports, romance, amusement, and so on, without any sign of being under coercion. But the government spends tens of billions of dollars annually (more than on national defense) on domestic weiwen, or “stability maintenance.” This category includes the regular police, courts, and prisons, but also censors and “opinion guides” for the Internet, plainclothes police, telephone snoops, and thugs for hire, whose work is to keep citizens in line. The targets are people who tend to get out of line—petitioners, aggrieved workers, certain professors and religious believers, and others. The stability maintainers are especially attentive to any sign that an unauthorized group might form. The goal is to stop “trouble” before it starts.

Weiwen does blanket coverage, but the blanket, most of the time, is soft. This is because citizens are well accustomed to monitoring themselves. They are aware of what kinds of public speech and behavior are to be avoided and they know that kicking the police blanket is not only dangerous but nearly always futile. People who do it, they feel, are odd, perhaps even stupid.

Those who do choose to stand out from the crowd, risking the label of “troublemaker,” immediately come into focus for weiwen. Police arrive for “visits.” They warn. They cajole. Failing that, they threaten and harass. Beyond that, they detain and charge with crimes. At each step they check with “superiors.”

It takes unusual character to stand up to this. People who do it are strong, stubborn, and, as their families and friends sometimes see it, high-minded to the point of obtuseness. The passions of some have been kindled by personal loss—an imprisoned brother, a murdered son, a razed home—while others are indignant primarily at the injustices they see around them. Many are idealists, oddly willing to risk personal safety because China falls short of what they want it to be. Some are lured by the image of heroism, even knowing that its price could be martyrdom. For many, there is a mix of these motives. In the Shadow of the Rising Dragon, a translation of essays from a book published last year in Hong Kong called Encounters with the Police, introduces fourteen such people.

A first question is why they are so important. They are a small minority, nonviolent, not wealthy, and not high-ranking. Many are women. Why are they not just marginal irritants—like “lice on a lion,” as the regime says (if indeed it says anything about them at all)? It is quite clear that they are much more than that, and that their audacity poses a genuine threat to the regime. Ironically, the best evidence for this comes from the regime itself—not in how it speaks of them but in how it handles them. It regularly “invites” them to tea and asks that they “coordinate” with police by sharing their plans; it monitors and if necessary confiscates their telephones and computers; it stations police at their doors (where, during “sensitive” times like anniversaries of the Tiananmen massacre of 1989, they remain around the clock).

Among its many anecdotes, In the Shadow of the Rising Dragon tells how, on a cold day in 2010, Ding Zilin, a seventy-three-year-old retired professor of philosophy, leaves her house with her husband, Jiang Peikun, to travel from Wuxi to Beijing. Jiang is ill. Two plainclothes policemen intercept the couple, tell them to get out of their car and into a police car, escort them to the Wuxi rail station, and then board the train to “share a compartment” with them. In Beijing, another car from State Security awaits them. Why all the attention, time, and expense? What does an elderly professor have that calls for such solicitude from a government that owns the world’s largest reserves of foreign currency and commands the world’s largest standing army?

Ding Zilin has—and it is all she has—the power to tell unapproved truths. Her son Jiang Jielian was killed when the army invaded Tiananmen in June 1989, and she later organized and led the Tiananmen Mothers, a support group for families of other victims of that massacre. She also became a mentor to Liu Xiaobo, who, just four days before her train ride to Beijing with the police, had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo. The prize was given in absentia because Liu remained in a Chinese prison, convicted of “incitement of subversion of state power.” These facts, at this “sensitive time,” were more than enough to assign police escorts to her. Their appearance was a symptom of a real fear that she plants in the minds of the men who rule China. What if her ideas get out and begin to spread?

Václav Havel, observing the response of the Soviet government to Alexander Solzhenitsyn in the 1970s, described

a desperate attempt to plug up the wellspring of truth, a truth which might cause incalculable transformations in social consciousness, which in turn might one day produce political debacles unpredictable in their consequences.

The mentalities of the Kremlin in the 1970s and of Zhongnanhai—the headquarters of the Chinese Communist Party and state—today differ in important respects, but this fear of truth-from-below, so well described by Havel, is something that the two groups share. It arises from awareness that public acquiescence to their rule is often performance more than conviction.

Official language, obligatorily true at one level, at another level is hollow. The rulers themselves need to deal with this language bifurcation. On the topic of the 1989 massacre, for example, they can announce that “the Chinese people have made their correct historical judgment” on the “counterrevolutionary riots.” But do they themselves believe this? If they did, would they not open Tiananmen Square every year on June 4 to allow the masses to come in and denounce the rioters? What they actually do, each year, is the opposite: they send plainclothes police to prevent any sign of commemoration of any kind. They plug that “wellspring of truth,” as Havel calls it. Ding Zilin and everyone else in In the Shadow of the Rising Dragon are plug-pullers.

The “superiors” who order the repression do not appear in the book. They operate behind the scenes. The people we see face-to-face with the plug-pullers are several kinds of underlings. They are normally young and more often male than female. They receive assignments and are paid to carry them out. They sometimes show respect for the people they are watching and speak frankly of “just doing my job.” They make it clear that they are not very well paid, and sometimes talk about their work schedules. Overtime work can be welcome if it entails following someone to a restaurant where state-issued coupons can be used to order fancy meals.

These books show us that they are sometimes not even official employees of the state, but ordinary people, including migrant workers, who are willing to work as temporary employees. There are companies that sell control services by contract. But no street-level police worker of any variety answers questions about policy; they refer these to superiors. Sometimes they don’t even use the word “superiors” but just point a finger upward to explain why they are doing what they are doing. One level above them are police who work in local stations or detention centers. These personnel are generally older, more experienced, and better trained in methods of interrogation. We see some of them in In the Shadow of the Rising Dragon. They have a certain latitude to make tactical decisions, but on weighty questions (like how to handle the travel of a truth-telling seventy-three-year-old professor) they, too, turn to their superiors.

What fills the pages of the book, therefore, is mostly the verbal stand-offs between two very different kinds of people: on one side, obdurate truth-tellers insisting on principle; on the other, people trying to do their jobs in order to earn salaries. What the two sides have in common is that each has an incentive to keep talking to the other. For the truth-tellers, the talk is a passion; for the police, it is a tool in control work. The symbiosis generates a language game that seems unusual by standards of other cases in the world to which it might be compared. Police in Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe were not nearly so talkative. They were brusque; business was business. In South Africa under apartheid, blacks dissimulated in their use of language in order to get by, and in that sense also played a language game, but there was nothing like the extensive give-and-take of the game that has evolved in recent decades in China. The matching of wits, the thrusting and parrying, and the posing (even while pretending not to pose, and even though both sides see through the pretending) all seem quite unusual.

For example, a young woman named Huang Yaling, two days after Liu Xiaobo’s Nobel Peace Prize was announced in Oslo in October 2010, went to the Norway Pavilion at the Shanghai World Expo to present a bouquet of flowers and a note that said “I love Norway.” The police noticed and invited her to tea. Here are excerpts of her interview with a male policeman. (This account, and another I draw on, appear only in the Chinese-language version of the anthology.)

“Did you go to the World Expo?”

“Yes.”

“To which pavilions?”

“Norway and Denmark. The others had too many people and I didn’t want to wait in line….”

“Was there anything you found especially memorable?”

“Oh, I met the director of the Norway Pavilion! He was as handsome as a movie star!”

“You’re married and you notice the good looks of some foreigner?”

“Why can’t I admire somebody’s good looks? My husband can enjoy the beauty of a foreign woman, and I bet you do, too!”

“I’m not married, so of course I can look at pretty girls. What about that director? You know what we’re asking about, so just cooperate!”

“I gave the director a bouquet.”

“And what did he do?”

“Accepted it.”

“What was the director’s name?”

“Aiya, what a pity! I forgot to ask the name. Do you know his name?”

“How would I know his name?!… What did you say when you presented the bouquet?”

“I love Norway and I’m offering these flowers to Norway.”

“Why give flowers to Norway?”

“I like Norway…. What else can I do?”

“Why do you like Norway?”

A few minutes later:

“All right, enough chit-chat, I’ll cooperate. You want to know why I brought a bouquet to the Norway Pavilion? I’ll tell you, but first you have to show me yourIDs….”

“Why do you care about our IDs? You’re still not cooperating. Do we need to get a subpoena?”

Ding Zilin, whose son was killed in Tiananmen Square in 1989 and who organized the Tiananmen Mothers, a support group for families of others killed there, in front of a shrine to her son, June 2008

“Who asked you to be so rude? Come on, let’s shake hands and then I’ll give you all the details.”

“We came to do our jobs, not to shake hands. Our job is to understand the situation. Why did you bring flowers to the Norway Pavilion?”

“OK, it was because of the Nobel Peace Prize.”

“What about it?”

“I was happy about it. Aren’t you? Aren’t you happy that a Chinese won the Nobel Peace Prize?”

“It’s not our job to talk about being happy.”

The words “our job” are significant. For police at this level, the job is to extract information. Their methods are remarkably similar nationwide—a fact that reflects their training. An important priority is to uncover a person’s contacts. Twenty years ago, this meant examining address books; today it means confiscating computers and cell phones. The police note e-mail addresses and read e-mail. They sometimes imitate a person’s style in order to send out bogus e-mail, hoping to lure unwitting responses. In interrogation, many questions are about a person’s associates: Who told you to do this? Who was with you? and so on. For their part, detainees often announce in advance that “I will talk to you, but in principle will say nothing one way or another about anyone else.”

Some methods for putting psychological pressure on detainees are standard, not only in China but around the world. People undergoing interrogation can be surrounded by questioners, placed under bright lamps, made to sit uncomfortably, deprived of sleep. They can be separated from colleagues and manipulated. (So-and-so has already told us everything; our reason for asking you what happened is not to learn what happened, because we know it, but to measure your sincerity, which will affect your punishment.) An abrupt change of topic can be an attempt to catch a detainee off guard. A sentence that begins, “In Marx’s socialist theory, regarding democracy…” can be cut off with, “When did you arrive in Nanjing?”

Threats are useful, and they come in many kinds: We can lock you up for years, you know. Would you like three, or four? How are your children? Going to school? Would you like them to stay at the same school? You are a lawyer; would you like to keep your license? Travel permissions—passports, visas, exit permits—are especially useful as levers. For “troublemakers,” China’s border has become a political toll booth. Whichever direction you want to cross it in, you need to pay a price. Some police threats are aimed at keeping the threats themselves secret. Detainees are asked to sign statements in which they agree not to “sully the image of the motherland” by talking about what has happened to them. (The contributors to the two books under review have obviously chosen to defy this instruction.)

Police the world over are familiar with the “good cop, bad cop” technique, and Chinese interrogators use it often. One moment an interrogator is saying, “We’ve looked at the material in your computer and all your online postings, and we sympathize with you”; the next, someone “poked my head, kicked the tiger seat [made of welded metal bands] and yanked my shoulders back and forth, ensuring that in my extreme exhaustion I couldn’t fall asleep.”

If extraction of information is a goal of police work everywhere, in China there is a twin goal—not found in most other repressive societies, past or present—and that is to change a detainee’s political attitude. This goal does much to explain why Chinese police want detainees to talk. Talking draws people out, engages them, and might be the road to changing their views—or at least their calculation of their own best interests. Hence much time is spent on questions like: Why do you bother writing articles like this? Isn’t China much better off than it was twenty years ago? Can’t you see that your friends have BMWs and you still have only a Toyota? Why go to prison? Don’t you want your children to have a father at home?

Teng Biao, a well-known human rights lawyer, had the question put to him bluntly. There were “two roads” for him to choose between: “detention, arrest, trial and prison” or “lenience for a good attitude, and…release.” Which would it be? “Just say a few words admitting error, even if you don’t believe it,” his interrogator advised, then added, “just as a favor to me.” Those last words were not merely an attempt to manipulate Teng Biao. They were in part sincere. If the official record showed that Teng Biao had achieved no “ideological transformation,” the interrogator himself could be faulted. Here we see one way in which detainees can gain leverage in arguments with police and sometimes even put them on the defensive. There are others.

One common tactic is to argue from law. China’s laws give rights to citizens, detained or not, and the police, although they violate these rights flagrantly and often, are obliged to pretend that they do not. At the rhetorical level China’s constitution is sacrosanct, and the distance between that level and what actually happens in interrogations gives detainees plenty of grounds for attack. During the verbal games that ensue, the police hold the trump card of knowing that overwhelming state power is always on their side.

Except for that, though, detainees almost always have the stronger position in argument because they know the law much better than the less-well-educated police do. Xiao Qiao, a regime critic who traveled to Sweden and then was barred from reentering China through Hong Kong in 2009, asks the Chinese border police, “Which part of the Regulations stipulates why a Chinese citizen can be prevented from entering her own country?” Receiving no answer, she presses further, demanding the return of books the police have just confiscated. What rule allows them to confiscate those books? Apparently beaten, but still bound to obey orders from superiors, the unfortunate border guard can only retreat to informal language: “Let it go, those few books aren’t worth anything, just buy some more when you get back to Hong Kong.”

The vulnerability of low-level police to legal argument from the people they detain explains their strong reluctance, shown repeatedly in In the Shadow of the Rising Dragon, to give their names or show their IDs. They feel trapped. On the one hand, they have been trained to detain people and extract information. On the other, they are not supposed to violate the law. In essence they have been given contradictory guidelines, but if they err, it is they, not the authors of the guidelines, who will take the blame. Some clever detainees come along, citing all the rules in the book, and ask for their names and IDs. What can they do?

Yet an appeal to the laws can go only so far if the police are the only ones hearing it. Hence a related tactic has emerged—that of extending the audience to bystanders. Xiao Qiao, arguing with border police over her right to reenter China, raises her voice sufficiently that others can overhear, and the police, perceiving her tactic, urge her to lower it. In courtrooms, an accused can sometimes turn a gallery into a sort of informal jury, drawing titters from it, even applause, by speaking common sense.

Xu Youyu, one of the editors of In the Shadow of the Rising Dragon, tells how police, after knocking on his door one night, tried to use the bystander effect themselves. As Xu stood in his doorway, talking to them but not inviting them in, they said, “Let’s not argue outside. It won’t look good to the neighbors.” They knew that ordinary Chinese fear the police and (whatever their private sympathies) tend to shun neighbors like Xu who receive police visits. The message to Xu, as he stood in his doorway, was clear: Do you want to be tainted by our presence here or will you let us in? Xu was already tainted enough that adding more would hardly make a difference, and in any case he knew that his neighbors largely respected him, so he turned the tables. He raised his voice and shouted that he hoped everyone in the building would know he was arguing with the police.

The Internet has greatly enhanced the bystander effect. Anecdotes about police misbehavior travel quickly online in China and become the focus of group discussion. After any report of confrontation between police and citizens, popular sympathy heads almost reflexively to the side of citizens. Smart phones, which have made photography much easier than before, have become important tools for activists and a new headache for police. Anything the police do might be on the Internet within minutes and visible to uncountable numbers of virtual bystanders—at least until Internet censors have a chance to take the photos down.

Publishing accounts of repression abroad can be viewed as looking for bystander sympathy overseas. (The books under review are an example.) Police in China seek to deter such activity with the threat that “patriots” do not cooperate with “hostile foreign forces.” Westerners sometimes shy away from contact with Chinese protesters out of fear that they might get them into trouble, but this is almost always a mistake. What usually happens, and these books show examples, is that detainees and prisoners in China are treated better, not worse, when the police know that the outside world is watching. The best course for outsiders is to let people inside China make the judgments about risks. If they reach out to you, or do things that invite international attention, to shy away is to second-guess them about what they know best.

Chinese protesters rely on the bystander effect because of an assumption that human beings, on average, share a basic civility that will naturally bring the sympathy of bystanders to the side of the aggrieved. This assumption of a common ethical bedrock is visible even in their face-to-face encounters with police. The verbal jousting of both sides observes some basic civilities, even if only for show. For example, a few days after a police raid, Ding Zilin, the seventy-three-year-old professor, was so shaken that she fainted and was sent to the hospital. The police then returned to ask her to sign a statement that said, “The patient fainted due to a dispute among family members.”

The police—not just the individual police but the system they work for—do not want it on record that they were the cause. The statement they offer her is a lie, to be sure, but the lie itself is evidence of a need to honor a common value: it is uncivil to cause old ladies to faint. (One could imagine them saying, “We are right, you are wrong, and fainting serves you right,” but they do not say this.) Ding Zilin objects to the statement they proffer. It is not true. But the police persist and ask her to consider their personal situations. A more factual record of the fainting episode would “cause problems” for them. Ding sees their point, and in the end assents, albeit grudgingly. She, too, takes bedrock civility into consideration.

In the Shadow of the Rising Dragon shows many examples of such accommodation. The two sides are always adversarial, and sometimes hostile, yet share a tacit understanding that there are certain values of decency that a person does not violate. Both sides use the assumption to gain advantages. Even a tough-minded lawyer like Teng Biao shows respect (or pretended respect) for the anxiety of police interrogators not to lose face by conceding that “some of the sentences and phrases in my essays were somewhat inappropriate” before he gets to his “but” clause and says what he really wants to say.

Still, it is worth keeping in mind the overwhelming unfairness of the administration of criminal justice. Jerome Cohen, a leading authority on the Chinese legal system, recently wrote that, quite aside from the formal criminal process,

The police also have a panoply of legally-authorized instruments at their command. They still detain millions of people every year—some repeatedly—for up to 15 days for each alleged violation of a very broad range of minor offenses against public order. They confine minor drug and prostitution recidivists for up to two years of rehabilitation. They continue to have the power to impose upon the more recalcitrant of such offenders, as well as a variety of dissidents, petitioners, democratic or religious activists and others deemed “troublemakers,” up to three years in a labor camp, with the possibility of a fourth year, under the notorious “Re-education Through Labor” regime that is currently undergoing revision. Many others are commanded to undergo periods of “legal education” in less rigorous circumstances. Since none of these restrictions on personal freedom is deemed to constitute “criminal punishment,” the police are not required to comply with the increasing protections provided by amendments to the formal criminal process, and rarely does court review or scrutiny by the procuracy provide relief against arbitrary police misuse of such “administrative” measures.*

Nearly everything is on the side of the police, but argument from decency, in the end, works better for activists than for their interrogators. Beyond its utility in face-to-face debate, it is the basis on which they appeal to bystanders. (No bystander in any country needs to be told that raiding police should not shock seventy-three-year-old professors into fainting.) Moreover it undergirds their advocacy of democracy, the rule of law, and human rights, all of which are assumed to be bedrock values that decent people do not oppose. When human rights lawyers call for the rule of law, the police, at least at the rhetorical level, have to agree. When activists call for democracy, the regime has no real grounds on which to differ; it can only grope for a distinction between “Western” and “Chinese” democracy. In short the jousting takes place on a slanted field. One side can say what it thinks while the other is obliged to pretend.

Chinese activists publish books like In the Shadow of the Rising Dragon outside China because they sense that the slanted playing field extends worldwide. They note that the world’s dictatorships feel obliged to call themselves democracies—the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, among others. By contrast, people who live in democracies (even if they sometimes admire the efficiency of dictatorships) never feel a need to pretend to the mantle of the other side—by calling themselves, for example, the Glorious Monarchy of India or the Authoritarian State of Canada. To Chinese activists, this rhetorical imbalance is a telling fact: for all the repression in China, including the many thousands in prison for speaking the truth, it implies that the fundamental assumptions of the world’s people, as embedded in ordinary language, are on their side.

11 11月

Over the last decade China has undergone a transformation. After the dark days of the Cultural Revolution, it has emerged as one of the twenty-first century’s most powerful economies, with millions of citizens now entering the middle class. Yet, despite these rapid changes, China’s human rights record remains abysmal, and a heavy shroud of secrecy protects the one-party system from accountability. InIn the Shadow of the Rising Dragon, Chinese citizens from all walks of life share their stories of brutality and oppression. While inconceivable in the West, public beatings, grueling official questioning, unexplained detentions, and house arrest have become common-place occurrences, requiring only a minor infraction to set into motion. Those that dare to push the boundaries of the totalitarian regime, including one essayist’s visit to the human rights activist Chen Guangcheng, are sentenced to life-long imprisonment, subjected to physical and psychological torture, and, frighteningly, made to “disappear.” What emerges is a pattern of harassment directed, not at opposition figures, but ordinary citizens who live in crippling uncertainty of their future. Edited by two Chinese scholars, both of whom have experienced surveillance, control, abduction, and detention, this is a probing and revealing look at life under the police state of the world’s most populous country.

Xu Youyu is one of the signatories of Charter 08, a manifesto drafted by Liu Xiaobo and other intellectuals calling for substantive political reform in China. Xu received a human rights prize on behalf of Liu Xiaobo in 2009, and he publicly supported Liu’s Nobel Peace Prize in 2010.

Hua Ze is also a signatory of Charter 08 and filmmaker that exposes China’s human rights transgressions. She has been detained in police custody and is currently a visiting scholar at Columbia University.

10 10月

各位老师,各位同学,各位朋友:

今天,各位能聚集在这里,与我一起讨论《遭遇警察》一书,我感到非常高兴和荣幸。我首先要感谢黎安友教授,他不但为我们主持今天的讲座,实际上,讲座得以举行,完全是由于他的倡议和帮助。

我还要对我的朋友古川表示特别的欢迎,他和妻子李昕艾,是本书的两位作者,多年来,他们受尽中国警察的迫害,两个月前,他们全家经过千辛万苦终于来到美国,从此可以过上平安、自由的生活,我和朋友们都为他们感到欣慰。欢迎古川!

编辑出版《遭遇警察》一书的念头产生于2011年春季。那时,北非一系列国家发生的“茉莉花革命”使中国当局感到恐慌,警察疯狂抓捕异义人士的恐怖气氛笼罩全国,许多朋友受到警察酷刑虐待的消息使我们既心痛,又气愤。我们认为必须让全世界知道在中国发生的人权灾难。我们认为,记录也是一种反抗,这种记录是未来在中国恢复和实施正义的基础。

本书的两名编辑徐友渔先生和我都有过遭遇警察的经历。徐友渔先生多年来被警察监控和骚扰,我在2010年被警察用黑头套绑架并秘密关押55天。这本书里收录了我们的故事。

书中另外20名作者也都有与我们类似的经历,例如,“天安门母亲”的代表人物丁子霖夫妇在刘晓波获奖后被囚禁的经历、作家慕容雪村去山东看望陈光诚被阻挠的经历、人权律师滕彪在2008年北京奥运之前被绑架的经历、法律援助机构“公盟”负责人许志永博士被逮捕的经历、人权活动家王荔蕻庆祝刘晓波获奖被拘留的经历、纪录片导演何杨被失踪的经历、记者雨声被毒打的经历、福建三网友言获罪坐牢的经历、参与营救陈光诚的英语教师何培蓉的经历。还有因签署零八宪章被喝茶、因看望良心犯家属被传唤、去天安门纪念64被扣留、向世博会挪威馆献花被谈话……作者中既有著名维权人士,也有普通网友,他们的经历代表了近年来中国人权恶化的各个方面。

我们知道,当今中国是世界上最大的警察国家。从2010年开始,中国的维稳经费已经超过了军费。所谓“维稳”就是政治警察对中国社会的全面监控。政治警察在中国被称为国保,从公安部、公安厅,到各县、市公安局都有这样的机构。他们可以凌晨从家里把你带走,而不必出示任何证件;所谓敏感时间他们会把你带到外地强制旅游;他们可以在你家门口、楼下、小区入口处安营扎寨,对你实施软禁;他们可以用黑头套绑架你,让你秘密失踪,对你实施酷刑。中国历史上与国保相似的机构有明朝的东厂、西厂和锦衣卫,世界上其它国家与国保相似的机构有纳粹德国的盖世太保、苏联的克格勃、东德的斯塔西等等。这些机构的相同之处就是具有超越法律之上的权力。

当然,今天中国的政治警察也有自己的特点:他们没有所谓的共产主义理想,他们也不会在意识形态的层面上跟对手辩论,他们只不过把监控对象当作项目。一个重要的监控对象就意味着一大笔经费。在这种情况下,他们并不希望监控对象停止维权活动,让他们失去财源,但又不希望他们把事情闹大,以免影响自己的前程。因此,有时候他们用黑头套绑架律师和记者,用各种酷刑施加身体折磨和精神羞辱;有时候他们又会乞求说:我跟你个人没有仇,这只是一份养家糊口的工作;偶尔他们还会透露一两句心里话:如果有一天中国民主了,我们也愿意为民主国家服务。有时候又会说:你们看不到中国民主那一天,在民主的前夜,我们会挖坑把你们全都活埋。还有时他们会苦口婆心地劝解说:何苦呢,好好过自己的日子,管那些干嘛?当你指出他们的行为违法时,他们会说:不要和我谈法律。法律不是挡箭牌。还有超越法律这上的东西。如果你问他,那是什么?他会说,我不能告诉你。

在遭遇警察时,受害者在法理和道义上占据了绝对优势。许多时候,遭遇警察的过程,就是在所谓“执法者”面前宣传和捍卫法律的过程。这些特点在《遭遇警察》一书中,有着非常淋漓尽致的描述。

我们决定要编辑这本书时,遭到了许多朋友的反对,当时红色恐怖弥漫全国,朋友们担心,这样一本直接揭露政治警察的书,会让我们的处境更加艰难。当时我已经来到美国,我更多的是担心徐友渔先生的安全,但他一无返顾,决定承担任何后果。因此,本书是在十分保密的条件下编辑完成的。有几次,当我们在讨论书稿时,徐友渔先生家传来敲门声,他马上告诉我,如果你从此联系不上我的话,请一定要将这本书完成。甚至在书稿交给出版社的前夜,他还一再叮嘱我:哪怕你听到我亲口对你说要停下来,你也不要相信,你一定要让书顺利出版。《遭遇警察》今年6月由香港开放出版社出版,由香港田园书屋发行,在出版之前既被纳入非法出版物入境黑名单,我们深感荣幸。感谢黎安友教授和科恩教授的推荐,目前《遭遇警察》正翻译成英文,预计2013年在美国出版英文版。当然,做为编者,我们最大的期望是有一天能在中国大陆出版,那将意味着中国开启了民主化的进程。

最后我想说的是,今天我们在这里讨论《遭遇警察》一书,有着特别的意义。两年前的今天,挪威诺贝尔和平奖委员会向全世界宣布,将2010年的诺贝尔和平奖授予中国异议作家刘晓波,我至今仍然清楚的记得,那天,我和我的朋友们怎样热泪盈眶、欣喜若狂。当天晚上,有十几名朋友因为举行庆祝活动而被捕。现在,两年过去了,刘晓波仍然在狱中,而他的妻子也已被囚禁在家,与朋友们失去联系整整717天。这就是中国–这个崛起的大国、和谐社会背后的真实故事。

9 10月

10月8日,《遭遇警察》(和谐社会的真实故事)一书的联合主编华泽在美国哥伦比亚大学召开新书介绍会。(摄影:陈天成/大纪元)

【大纪元2012年10月09日讯】(大纪元记者陈天成纽约报导)由中国大陆知名学者徐友渔和旅美纪录片导演、作家华泽共同主编的《遭遇警察》(和谐社会的真实故事)一书6月上旬在香港出版,10月8日,该书联合主编华泽在美国哥伦比亚大学召开了新书介绍会。介绍会由美国汉学家黎安友(Andrew Nathan)教授主持,胡平、王军涛等知名民主人士和多位哥大学生出席。

该书记录了中共国保警察的暴虐、践踏法律和侵犯人权的行为,中国公民受到的压制、侵凌,以及大陆中国在“和谐社会”外衣掩饰之内的撕裂和高压。

据了解,这本合集的起源可以追溯到中国大陆的“茉莉花集会”时期,当时有很多网友、维权人士、知识分子被警察拘禁、殴打、约谈。该书的联合主编徐友渔曾表示:“这些警察的无理、可笑、暴虐、荒谬,远远超出了人们的理解和想像,不为警察的种种恶行、受害者的种种遭遇和感受留下记录,于历史是一种缺陷。”因此徐友渔与华泽两人经过一年多的精心筹备,在高度保密的情况下编辑组稿,最终成功出版该书。

华泽说:“出版这本书前曾遭到很多朋友的反对,因为它直接揭露的是警察的内部,他们担心我们的安危。但是徐友渔先生表示,不惜一切代价也要让书出版,他曾说:‘如果我被带走,如果不能再和我联系,你也一定要把这本书完成出版,哪怕有一天你听到我亲口对你说要停下来,你也一定要继续出版。’”

全书收集了21位内地维权人士与国保打交道的故事,讲述他们遭遇过的国保、警察的行径。

华泽说:“这些政治警察有超越法律以上的权力,他们并不像东德、前苏联那时的政治警察有太多意识形态的东西,他们也没有信仰共产主义的理想,他们更多的是把维稳当成一个项目,一个异议人士对他们来说意味着一笔钱。他们既不希望异议人士把事情搞大影响他们的前途,又不希望异议人士停止维权活动,因为停止维权活动也就意味着他们少了一笔维稳经费。”

正因为这样,国保警察们表现出了各种各样的行为。

“这些政治警察一方面用法西斯、黑头套的手法将异议人士绑架、失踪、实施酷刑,一方面在和异议人士打交道的过程中,明明是非法传唤,他们说是‘喝茶’,敏感时期把人软禁、带出北京,美其名曰‘出去旅游’。”华泽说:“他们还讲‘我们之间没有什么个人的仇恨,我只是一个饭碗,不要为难我,将来民主了我也可以为你们工作。’这样的话。但是另外一方面,他们也说‘你们是等不到民主的那一天的,因为到那一天的前夜,我们就会把你们这些人全都埋葬。’”

书中供稿作者之一、目前在哥大任访问学者的中国异议人士古川也来到介绍会现场,讲述了他在2011年“被失踪”63天期间被关3个黑监狱、遭国保警察“黑头套”、“剥夺睡眠”、“酷刑”、“性骚扰”和“非法提审”的经历。

(责任编辑:索妮雅)

30 7月

原刊载《阳光时务》

“哪怕你听到我亲口对你说要停下来,你也一定要继续出版。”学者徐友渔在《遭遇警察》出版之前,一字一句地对共同主编该书的华泽交代。他担心在最后关头,出版计划被国保发现,并强迫他停止发行。

“哪怕你听到我亲口对你说要停下来,你也一定要继续出版。”学者徐友渔在《遭遇警察》出版之前,一字一句地对共同主编该书的华泽交代。他担心在最后关头,出版计划被国保发现,并强迫他停止发行。

他的担忧没有成为现实,6月4日,该书在香港如期出版。全书收集了21位内地维权人士与国保打交道的故事,字里行间并没有太多的腥风血雨,大多数作者甚至在用调侃的语气讲述自己面对过的国保、警察。

因为正如华泽所说:“这本书的重点不是要说明警察的残酷,或者侵害人权的严重。我们想要记录的,是警察在这个社会中无处不在,深入到普通公民生活的方方面面。”

记录也是反抗

这本合集的起源可以追溯到去年内地的“茉莉花集会”,因为不少网友、维权人士、知识分子被警察约谈、拘禁甚至殴打,警察国家已经凶相毕现。而在徐友渔看来:“这一阶段警察行为的无理、可笑、暴虐、荒谬,远远超出了人们的理解和想像,不为警察的种种恶行,受害者的种种遭遇和感受留下记录,于历史是一种缺陷。”因此徐友渔与华泽两人,一个国内一个国外,精心筹画了一年的时间,自行组稿,终于成功出版。

只是这本书在面世之前,已经被列入内地出版物入境的黑名单,必然被很多读者错过。但是华泽希望有一群人要看到:那就是书中提到的每一位国安、国保、警察、保安,她甚至尝试著与出版社商量,给这些人每人赠书一本。

书中的主角既有如律师许志永、工程师游精佑这样的专业人员,也有教授徐友渔、老师何培蓉这样的知识份子。他们都来自各行各业、不同的阶层。

而这也正是当初华泽挑选文章时特地考虑到的一点:“这些人都只是普通的公民,而且参与的维权行动都是合乎法律、也不是依靠某个组织而行动的,他们的姿态温和、理性,因此与往常想像中的异议分子有很大不同。”

华泽本人也是其中一个例子,作为纪录片导演,只因为拍摄人权纪录片以及连署支持刘晓波的声明,而遭警察殴打、拘禁。这些公民唯一相同的是,他们遇到了同样的一堵高墙:警察。

中国特色的政治警察

这些政治警察的形象是千奇百怪的,但同时也是平凡、普通的。在两位编者眼里,当代中国政治警察并不像文革时期、甚或东欧秘密警察那样充满信仰,他们不再以正义的捍卫者身份出现,在背后蛊惑他们的是金钱的利益。

“这些警察只是把我当成一个可以拿到经费的项目,连他们自己都不相信自己是正义的。”当华泽被拘禁在江西的宾馆,当地国保用这样的一句话“欢迎”她:“我们和你之间没有任何的冲突,只是受到了公安部的命令。所以住在一起的时候,只是希望您不给我们惹麻烦。”

徐友渔在本书前言写到:“中国警察既不神秘,也不威严,中国公民遭遇警察不是偶然、个别、例外的,而是大量、经常的,不是在暗处,而是在明处。他们可以打个电话就上你家,或者不打电话就来,长久以往变成常客;他们可以定期请你喝茶、喝咖啡、进饭馆,俨然成了酒肉朋友;他们可以在被监视物件的家门口、楼下、社区入口处安营扎寨,人手不够时大量雇佣保安、城管、农民工,每人每月只给一千多元,为了监视一个人雇八个人,三班二十四小时不间断。这时警察像包工头,拉起一支乱七八糟的临时工队伍。”

当代政治警察的第二个特点,便是软硬兼施,华泽接受采访时说道:“之所以这样,部份原因就在于这个国家需要监控的公民太多了,现在维稳费用不是都超过了军费了吗?”

“对人们的监控和短期扣押出于‘防患于未然’的考虑,出于‘千万别在我这里出事’的心理,出于‘一定要平安度过这段敏感期’的命令。对个别人士,他们采取柔性方式:明明是扣捕和拘押,却要安排成旅游,入住宾馆,呆在度假村,他们要人们相信这是‘人性化’措施,其实是想规避法律程式方面的难题;而对于绝大多数监控对象则凶相毕露,打、骂、侮辱、虐待,甚至对于身体残疾或身有伤病的人也是如此。”

也正因为警察本身并不全都唱白脸,所以本书另一个让人忍俊不禁的地方是维权者对警察的不同想像:滕彪把他们按照ABCDEFG来排列;刘沙沙给他们取了“中统特务”、“尖下巴”、“脑残”的名字;记者雨声则称呼他们为小楚、小胡、阿陈。

出版该书的开放出版社总编金钟则希望,书中那些站在第一线的勇士们的努力,能够成为推动中国从警察国家走出来的庞大动力。

29 7月

中国知名公共知识分子徐友渔和纪录片导演华泽编的这部书最初的题目是:『遭遇警察—“和谐社会”里的故事』,香港开放出版社出版的时候把标题改为『遭遇警察—中国维权第一线亲历故事』。前者似更富有寓意,后者则凸显见证。全书共收集了21位作者的22篇文章,作者们娓娓谈来,引人入胜,然而读者则不由得惊心动魄起来,不由得恐惧起来。也许骤然间你会获得一种悲壮感,一种感同身受的命运感。因为,这里的作者和编者本身就是受害者,本身就是见证人。

这个真实的社会里警察无处不在,编者在前言里简要地勾勒出中国独特的警察现象:“与苏联东欧秘密警察的活动方式不同,中国警察既不神秘,也不威严,中国公民遭遇警察不是偶然、个别、例外的,而是大量、经常的,不是在暗处,而是在明处”。于是,那些本来与熟人、与朋友交往的日常情景:喝茶、吃饭、旅行、度假,在这里都具有了特别的含义,恐吓和威胁在这里明目张胆,但警察表面上似已失去了昔日的威严,以日常生活的方式向你“打招呼”。请你免费住旅馆,原来你已被失踪。请你住进度假村,原来你已经寸步难行。

不言而喻,这是一个警察社会。然而,作者的可贵之处就是用笔把自己奇特又日常的遭遇记录出来,从而成为刻骨铭心的永久性记忆。也许数十年过去后,某些观念会过时,然而作者笔下那些罪恶的瞬间,黑暗的片刻却永久性的让人触目惊心:华泽女士拍完纪录片回家途中突然遭遇警察蒙面绑架,滕彪从书店出来,突然间被塞进警车带走……这些日常而又不平常的历史场景,不仅是现实的、也是历史的,不仅是社会的,也是启发人思索不已的当代寓言。这是一段珍贵的记录,作者把它们记下来,让活着的人战胜遗忘,让未来的人不要忘却。

本书的编者之一,目前在美国哥伦比亚大学做课题研究的华泽(笔名灵魂飘香),为我们谈了编著这本书的缘起和经过。

法广:出这本书的动机是什么?是不是和自己的经历有关,我们都知道,你曾经遭到警方绑架,你关于自己遭遇的这段经历也收到了这本书里面?

华泽:这本书是我跟徐友渔老师合编的,我们都有同样的遭遇。我有被绑架,被长期监禁的经历,徐老师也被警察长期监控,经常被骚扰,被谈话。所以,这首先是跟我们的经历有关系的。再一个就是我们周围有很多朋友都有相同的经历,我们听到的感受到的非常多。另外一个原因就是去年有人在网上发帖子号召进行“茉莉花革命”,随后,中国有大批的维权律师,维权人士,自由知识分子都被秘密关押,被逮捕,被刑拘。当时消息传来,那个时候我已经在美国了,徐老师在国内。我们都非常震惊,很悲愤,觉得我们应该对这一件事情做出反应。我们经常在网上讨论,后来决定出书,这是我们力所能及的。虽然我们的这种做法不能阻止他们肆意滥用公权力,但是,我们可能能够把这些不为人知的、在黑暗中的事情暴露在光天化日之下。

法广:书的名字很独特,为什么要起这样一个名字,叫“遭遇警察”,副题最早叫做“和谐社会的故事”,咋看起来,让人觉得平淡和平和,以为是个人的命运遭际,其实不然啊?

华泽:我们一开始就定下了这个题目。对于“警察”这两个字,后来有人提出应该叫“遭遇公安”,“遭遇国保”等等。其实,“警察”这两个字的意义就是我们在书的前言里说的,就是现在这个国家已经是一个警察国家了。放眼国际社会,能够称得上警察国家的,在现代可能就只剩下纳粹德国和前苏联。用这个词,就预示着这是一个警察国家,用公安什么的,这个词就不能有国际化的视野。就无法让别人明白。

我们在『遭遇警察』这本书里选择的是各种各样不同的人,有一点样本的意思。比如有维权律师,也有普通网友,还有知识分子和天安门母亲。各种各样的人的遭遇,程度也不一样。有的是坐牢的经历,有的被绑架过,有的就被“喝喝茶”,有的被传唤了几个小时。这些不同的经历,我们想通过它来反映,在中国社会,警察已经深入到每个公民的生活当中,每一个人都可能随时随地遇到警察。

法广:你能把这本书的内容给我们概括地介绍一下,在你看来,这本书的特色是什么,你们在选题和编辑时考虑到哪些因素?

华泽:我们编这本书时并不是想说这个警察国家它有多么地残忍。关于残忍,几十年在中共统治下,已经表现得淋漓尽致了。这本书主要想反映警察的无处不在,他的触角已经深入到社会的各个细胞。文革期间,我们说这是一个专政的国家,现在说这是一个警察国家,就是说他的触角深入到每一个细胞里面,只要你稍微有一点让他们觉得不满的,你就可能会遭遇到警察。

还有一个特点,它的这种无处不在表现得不像过去那样,就是说他代表着一种意识形态,他来就是非常威严地告诉你,你如何如何触犯了法律。不是这样的,现在很多情况下,他就直截了当地告诉你说:你不要给我谈法律,我也就是靠这个吃饭。变成这样了:有的人把它当成项目,有的人把它当成养家糊口的方式。

法广:这本书开宗明义,就叫『遭遇警察』,现在书出来了,书的遭遇如何?能不能进入中国大陆发行?

华泽:我们出书肯定最希望能在中国大陆出版和发行。我们的目标当然就是中国的普通的读者。可是我们这本书不可能在中国大陆出版。而且,在这本书还没有发行之前,就已经上了黑名单了。朋友给我们看了,就是一个入境的黑名单。它应该是发给海关的,上面并不列出书名,只说哪些出版社和那些作者是不能入境的。我和徐友渔都上了这个黑名单。不知道他们是怎么知道的。因为,刚开始想做这本书的时候,徐老师一直在国内,我非常担心他的安全问题,当时我们曾经试图组一些稿,可是朋友们说绝对不可以做这件事情,太危险了。那时候非常紧张。我们讨论了半天,徐老师决定承担这个风险。但是我们不希望在这本书出之前就被他们发现,就采取了非常严格的保密方式,从起这个念头,去年春天到现在,差不多一年了。这一年里面,每次警察去找徐老师,他都担心可能会因为是这件事情。他事先叮嘱我如果不能跟我联系了,我应该怎么样做等等。可是事后每次他都告诉我说,他们没谈这件事情。一直到交给出版社了,就是出版前夕,我们看到了这份黑名单,也许是从印刷厂或者其它渠道传出去的。

法广:这本书你和徐友渔亲自编辑,现在已出版了,如果我问你,书中的故事,除了你自己的,作为编者,哪些给你留下的印象最深,哪些让你久久难忘?

我觉得每一篇都很难忘,因为我们也是经过很多的筛选的。当然,最让我难忘的一个是滕彪的『我无法放弃』。这是我刚刚被警察监控,进入到这个领域的时候,我就看了他的这篇文章,给我印象特别深刻。这篇文章对于我可能相当于一部教科书吧。事先我能做好可能会遭绑架的准备,这篇文章也是一个指南之一。

法广:这本书的前言说,中国警察无处不在,那是不是部分地解释了这本书的题目,因为警察无处不在,警察自动地就成为这本书的主要角色,换句话说,也就成为今日中国的一种恐怖的景象?因为有些日常行为,比如喝茶,见面呀,这些本来是朋友间的、熟人的交往,也和警察们发生了关系?

华泽:是的,现在中国的维稳的机制变得越来越庞大,把非常庞大的人群纳入到它的这个维稳的范围中,一开始比如说维稳的对象只是法轮功学员,是访民,现在就可能是所有人了。比如你在网上发了一个帖子,他们认为你这个帖子敏感,他们可能就要请你喝个茶。我们说的喝茶不一定是真的喝茶,就是一种秘密地传唤,非法地传唤,不给你任何手续,也不出示任何证明。好些人,比如我原来的一些同事和朋友认为,因为你们关心政治,所以才会这样。其实不一定的。比如在前纳粹德国,很多人当时以为自己不是共产党,也不是工会会员,我不是什么,他们不会来找我的。可是不一定的。可能有一天,你不知道,你是在什么地方触犯了什么。你可能悄悄地说了一句话,或者在电话里发了一句牢骚,你就可能会被警察光顾的。

法广:我们台以前报道过你的遭遇,你的故事。最后,你愿意不愿意简单地告诉我们的读者,你近来在做什么,你绑架获释后的又有哪些特别的经历?

华泽:2010年我被绑架,然后释放之后,我主要是写了我被绑架的经历,叫『飘香蒙难记』。我写了这篇文章,又受到很多骚扰,那段时间感到身心疲惫。当时还有美国的签证,就到了美国,想休息一两个月。可是,我出来以后,很快有人就在网上发出号召茉莉花革命的帖子,接着就有很多很多的朋友被秘密关押、被失踪、被绑架、被逮捕、被刑拘,甚至有人被起诉、被判刑。那段时间,国内朋友通消息时就说你现在可能不能回来,回来比较危险。这个时候正好哥伦比亚大学人权所邀请我做访问学者,那么我就把这本书当成了我的课题。所以,这一年主要的工作,基本上就是在编这本书。

中国人与警察的遭遇远远没有终结,作者在前言中指出:“本书记录的中国公民与警察的遭遇,只是历史真相的一个侧面,远远不是全部”。而且,“我们知道高智晟、郭飞雄、刘晓波、艾未未等重大案例,我们无法把他们的遭遇包括进来,也没有条件约请他们的亲友提供描述他们遭遇的记录”。 那么,大家有理由期待花泽和她的朋友们的下一部书早日问世。

近期评论